My thanks to Touch Consulting, and the Joy FE community, who makes the #FestivalFridays conversations possible. A learning network of courageous practitioners who are resistance to the established norms that can hinder the well-being of those struggling to flourish within education.

I enjoy the enthusiasm in the lead up to a presentation, there’s an energy that comes of being wanted. A thrill, and anxiety, that is motivating and exhausting in equal measure… I’m no longer surprised that the linear story I have in my head, put into text with supporting 34 snapshots, rarely ever matches the messiness of the conversation in the room. Years of keynotes do not compare well to the joyful chaos of building understanding in the room.

I started with a trigger warning, not because it’s fashionable, but because we know that 9 in 10 disabled people report hate crime every year. Therefore, we can assume that violence is recognised in most rooms, because one in ten individuals can identify as disabled- should they wish. I explained that while the story was mine, we were having a professional dialogue, so the storytelling was framed by evidence and theory [Disability Studies among others].

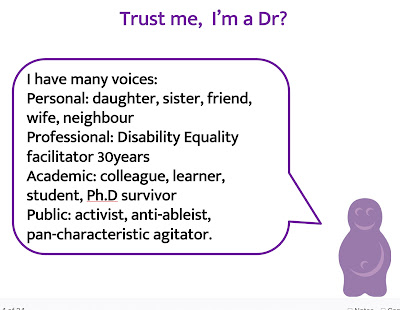

I am sharing professional wisdom - that’s 30+ years of conversation. Like discussions about critical race or gender, ones about critical disability is a specialised subject with an extensive knowledge base [you wouldn’t stop random individuals on the street as it could be potentially traumatising].

Othering emerged fast as an emotional tension in the room; talking about disability is uncomfortable because the ‘them’ and ‘us’ continuum becomes more visible when we talk about who’s in/out. I too get tongue-tied and stutter in the choice of ‘them’ and ‘us’. Should I identify as a disabled author, or am I writing as an equal scholar in a discipline I've studied for decades - leadership. I'd prefer to let people identify as Disabled or non-disabled, rather than assume ... get it wrong.

Clearly, there’s more to it than what’s wrong with you… what about society? Where’s the difference, mobility, impairment, glasses, dyslexia? The question is do you identify, surely? Do you face ableism? One in ten of us may choose, that's a huge group.

Truth is terminology, or lack of it, hinders definition or clarity. A single word, disability, covers so many notions, it’s not surprising we struggle to find accuracy - let alone alignment or agreement. Words fail when it comes to nuance: label, diagnosis, politics, difference, impairment, network, community - disability has been used willy-nilly and every which way. To define ableism, I have used ortho-toxic, a portemanteau term, to describe the violent ideas and assumptions imposed on the disabled population. It means I don’t have to point a finger - at individuals or groups - people can identify as they wish. It’s clear it’s not always a reflection within easy reach, many will say they’ve never encountered sexism, for example, others say islamophobia appears the minute they cross their own doorstep.

It is surprising how many of us can ignore the subject of disability altogether, while others see it as an aspect of human diversity, yet more will recoil in horror or embarrassment… how dare you bring your elephant to the room… it’s hard to identify, as I explained, you run the risk of being dismissed [see Kafer on testimonial injustice].

Misrepresentation is evident in the textual world, where a noticeable silencing tells us that disabled people are untrustworthy. Disabled people are not recognised as authors, thereby denied a voice in mainstream debates that impact them negatively. Rarely referred to as writers with authority, creators of knowledge, in documents that largely reinforce their marginalisation instead.

Why would I lie?

This shape of silence is hard to describe but essential to describe the framing of d/Disabled authors in text. Selective editing of 1st hand experience, giving a framed story with a medicalised view of the person as the problem. Denying the systemic, institutional and social violence reminiscent of #MeToo and #BLM campaigns. It seems the paid-pen exercises its privilege, not exclusively held by white, professional men, but under a more omnipresent cis/white/elitist gaze. Resistance is far harder for the pens held by those not fighting racism, classism, sexism, homophobia, religious intolerance or prejudice linked to partner and family choice. The 9 protected characteristics should be equitable categories, but cumulative impact is rarely articulated in guidance. If disability is mentioned on reference lists, details are shed, and divergent voices are erased, as unconsciously layers become shorter to save wordage in the final draft. Where disability may be ninth in a list in the introduction, sometimes mentioned in the review, it then disappears in discussion… as for the reference section watch the tumbleweed. Of course, disabled writers may not identify for fear of having their texts judged harshly, and many write from 1st experience rather than with activism or accountability to other disciplines and professional journals. Disability in title rarely translates to existing knowledge, or knowers in the narrative. Assumptions and bias obvious in the individualising, personalising, uniqueness of condition or individual. This writes away the dimensions of institutional and systemic discrimination and societal disadvantage.

The impact of silencing is apparent where assumptions become myths reinforcing the stereotypes that themselves grow from ignorance - not experience or research evidence. The belief that a mere few need consideration, therefore the problem can be attributed to the unlucky or the undeserving. The omission in disciplinary and professional texts, forgotten in the granular, or believed to be the problem [cost] of another department, profession, or institution. The idea that there’s a line to be drawn between those who can and those who cannot fit into the system; the rules imposed keeping some watching from afar and others further yet beyond the walls. Finally, the dehumanising of those then viewed as public property; from research to the pool-side, experience is used, revised or demanded as it is considered both cheap and devoid of typical privacy - no consent or care required in the probing.

Accountability, or rather the legitimacy gap that is articulated here, denotes a breakdown of trust where reputation lacks any acknowledgement to the disabled population, disability equality or the interests of the disabled people’s movement [D/deaf and Disabled People’s Organisations]. Where legitimacy theory can be defined as the ability to respond to civil groups it will need to demonstrate an intent to address their interests fully in organisational accounts - and society’s storytelling.

As Oswick et al. put forward, a radical travelling theory is one that moves beyond its own domain of production to be adopted by existing ones with equal measure. A theory that adopts anti-ableism in its intent, therefore, needs broad applicability [Social Model]; so that it can effectively begin ‘a process of repackaging, refining, and repositioning a discourse (or text) that circulates in a particular community for consumption within another community’ (2011, p. 323).

From the sadness at birth, testing for school, a poor practice that stigmatises, barriers, denigration and rejection in the workplace, made victims by justice and barred entry to transport, housing and leisure, the reduction of the human rights agenda applied to disabled people is reduced to care and cure, and adds massive cost to society. Plus, there's no price on the emotional burden imposed on many!

Trust me!

Just ‘any effort’ isn’t sufficient, the imperative behind practice needs to be with the right effort and have deliberate intentionality. While good, best and proactive practice sometimes equates, addressing ableism doesn’t happen by accident while chasing efficiency. Because being better at treating people fairly means recognising an agenda broader than financial value. Divisible or conditional human rights is a nonsense! Cutting down on worth and values, will not achieve more equitable culture(s). Practice will need to change to avoid the very activity that compounds the structural discrimination and the impact of inequality experienced by so many. Addressing ableism is like tapping your head while rubbing your tummy, different actions are required at individual, team and organisational levels.

Bibliography

Aikaterini Malli, M., Sams, L., Forrest, R., Murphy, G., & Henwood, M. (2018). Austerity and the lives of people with learning disabilities. A thematic synthesis of current literature. Disabiity & Society, 1412-1435 .

Anderson, T. (2017). Telling the story of disability. Retrieved 11 10, 2018, from Washington state university libraries: https://research.wsulibs.wsu.edu/xmlui/handle/2376/12238

Beauchamp-Pryor, K. (2012, 6 20). From absent to active voices: securing disability equality within higher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(3), 283-295.

Beresford, P. (2003). It's our lives, A short theory of Knowledge, Distance and Experience. London: Citizen Press / Shaping our lives.

Campbell, J., & Gillespie-Sells, K. (1991). Disability Equality Training: a trainers guide. London: CCETSW.

Chapman , L. M. (2013). A Different Perspective on Inclusive Practice Respectful Language . Huddersfield: EQTraining Publishing .

Chapman, L. M. (2016, feb 26). The words that bind us . Retrieved Aug 12, 2017, from The Language Of Respect : http://languageofrespect.blogspot.co.uk/2016/02/the-words-that-bind-us.html

Crow, L. (2014, 8 28). Scroungers and Superhumans: Images of Disability from the Summer of 2012: A Visual Inquiry. Journal of visual culture, 13(2), pp. 168-181.

Disability Rights UK. (2012). The Equality Act and disabled people. Retrieved 11 13, 2019, from Disability Rights UK: https://www.disabilityrightsuk.org/equality-act-and-disabled-people

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education. San Francisco: University of Michigan Press.

Ellis, K., & Kent, M. (2016). Disability and Social Media: Global Perspectives [Kindle Edition]. abingdon: Routledge.

Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2016). Crime and disabled people: Measures of disability-related harassment 2016 update. Equality and Human Rights Commission. Equality and Human Rights Commission.

Fenney Salked, D. (2016). Sustainable lifestyles for all? Disability equality, sustainability and the limitations of current UK policy. Disability & Society, 447-464.

Frame Works. (2016). How to Talk About Disability and Human Rights. Frame Works. Washington: Frame Works.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford university press.

Fullan, M. (2011). The Moral Imperative Realized. Thousand Oakes: Corwin sage.

Goodley, D. (2012). Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hall, A. (2016). Literature and Disability (Literature and Contemporary Thought) [Kindle Edition]. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hawley, K. (2012). Trust: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) kindle edition. Ashford: OUP Oxford; 1 edition .

Hughes, B. (2015, Sept 11). Disabled people as counterfeit citizens: the politics of resentment past and present'. Disability and Society, 14.

Hybels, R. C. (2017, 12 13). On Legitimacy, Legitimation, And Organizations: A Critical Review And Integrative Theoretical Model. Academy Of Management Proceedings, 1995(1).

Inclusion London. (2020). Disability hate crime . Retrieved 4 4, 2020, from https://www.inclusionlondon.org.uk/campaigns-and-policy/facts-and-information/hate-crime/

Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

McRuer, R. (2006). Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (Cultural Front) [Kindle Edition].New York : New York University Press.

Orton, J. D. (1997). From inductive to iterative grounded theory: Zipping the gap between process theory and process data . Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13(4), 419-438.

Oswick, C., Fleming, P., & Hanlon, G. (2011). From borrowing to blending: rethinking the processes of organizational theory building . Academy of Management Review, 318–337.

Papworth Trust. (2018, 5 5). Papworth Trust's Disability in the UK: Facts and Figures 2018. Retrieved 8 16, 2018, from Papworth Trust: https://www.actionduchenne.org/news/papworth-trusts-disability-in-the-uk-facts-and-figures-2018

Pennycock, A. (2010). Language as a Local Practice . Abingdon: Routledge.

Perry, D. M. (2016, 2 25). How “Inspiration Porn” Reporting Objectifies People With Disabilities. Retrieved 11 11, 2018, from Medium: https://medium.com/the-establishment/how-inspiration-porn-reporting-objectifies-people-with-disabilities-db30023e3d2b

Qa Research. (2017). ‘It’s broken her’ – Assessments for disability bene ts and mental health 3. Rethink Mental Illness. Rethink Mental Illness.

Sergiovanni, T. (1985). Landscapes, mindscapes, and reflective practice in supervision. Journal of curculum and seprevision, No 1.5-17 5.

Slorach, R. (2015). A Very Capitalist Condition: A History and Politics of Disability. London: Bloomsbury.

Smith, D. (2016). Disability in the United Kingdom. Papworth trust. Cambridge: Papworth trust.

Sommers, J. (2017, 8 22). Disabled People's Right To An Independent Life Being Eroded By Cuts, Equalities Commission Warns . Retrieved 11 29, 2017, from Huffington Post: http://m.huffpost.com/uk/entry/uk_599c473ce4b06a788a2bef3

No comments:

Post a Comment