I am lucky enough to have a friend who can spin a proper yarn. Her phone calls transport me, to different lands with exotic players... who knew the world of education could be so enthralling. I hope I am a rewarding audience, I to gasp or giggle in all the right places. The performance is a shared experience, the tale weaved between us. I never think to question the truth of the words, within them our reality is created. A joy and a pleasure. To miss quote Robison, without me she wouldn’t be a storyteller - just a woman speaking into the void.

I often think the legacy of scientific research is a belief in one truth. I am thankful the social sciences have offered us a plural. I hope we’ve all had the joy of learning things that tilt our private worlds on their axis. With implications falling like dominos in fluid sequential movement – rarely tbh.

My such moment was being told the story of the Disabled people’s movement, its storytellers and its truths. The Social Model was presented as a truth, one was new to me, part of an alternative vision. Since then I’ve discovered a world full of tellers with stories of equally compelling landscapes. All have a shared perspective, a direction, of a redefined world. One I’d complacently never questioned.

The story about the Social Model was so powerful it was hard to ever speak of disability without thinking of the pioneers. In a day I’d jumped from 6 to 9 never then able to see one without the other. It didn't erase other stories or tellings, but sometimes spoke a truth to my own experience. Unfortunately, while in my heart I still felt I am a problem having impairments, now occasionally if I concentrate I can think myself free of the oppression Disabled people face – the Medical Model. Every tale that speaks to the prejudice, institutional discrimination and global inequality - reinforces the truth of my story in any number of small ways.

Why do I slip back in times of stress, fatigue or difficulty? Well unfortunately tales about disabled people - in society’s stories - are far more available and plentiful which makes them difficult ignore or contradict. As Saint or Sinner the presentation of disabled people is polarised. Therefore, it requires a lot of effort to stand against the weight of common assumptions. That is because unthinking is much like driving a cross-wired car, turning left to go right only works while you are vigilant. The minute you rely on instinct - driven by bias - you are off the road or in oncoming traffic. CRASH!

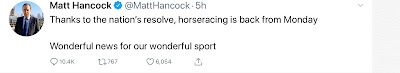

Unthinking is far harder than going along with an existing storyline. Across many cultures, in tales disabled people are described as costly and/or deficient. These myths are woven into everyday stories, so deeply they are barely noticeable. And while many people have come to believe that these tales need serious contradiction, more subtly Disabled people themselves are treated as unreliable tellers. This maybe because our experience seems too unusual, it jars with the shared story. The alternatives Disabled people put in words chimes against the assumptions told about us. So like the car we crash against both truth and teller. Recent personal examples:

◦ I told a friend I lived in West Yorkshire - "... it doesn't exist" he said.

◦ I answered my mum’s name was Caroline - the woman asking said "no it’s Claire".

I could go on... and I’m not denying I talk utter rubbish on occasion. But you’d be surprised how many times a week people correct me purely because my truth doesn’t chime with theirs. It’s a six they cry, in the face my truth - if not indisputable knowledge. I particularly like the wagging finger that goes with "if you lot had done your activism properly!!” or the "if you could agree with each other”. Yes, because Martin Luther King Jr’s dream took a decade to achieve and all feminists have one definition of sexism!!!!

In own research I felt I had to present the literature chapter as an analysis because in matters of human rights the stories I read appeared distorted. More widely I feel Disabled people haven’t been trusted as storytellers - even on matters of disability. One week I read 800 papers I had found by typing ‘disability’, ‘disabled people’ or ‘people with disabilities’ in the search criteria. Only about 2% even alluded to a political strength, a theoretical view, or the interests of Disabled people as a group - a shared voice. I was actually shocked how much was written about disability without legitimacy - as above, clearly West Yorkshire doesn't exist.